Is the most sustainable building the one that already exists?

By Martina Goluchova

We have recently submitted a planning application for a replacement dwelling in Bristol. Bristol City Council declared a climate emergency in November 2018. Setting all other planning issues aside, the first question we had to ask ourselves, with the climate emergency in mind, was: Is it acceptable to demolish a building and replace it with a new one?

Our clients were adamant that a new build was the only approach that would satisfy their brief. They have previously retrofitted their home and, although it worked well, there were ultimately many compromises. This led them to question whether building a new home using low-carbon natural materials, to the highest airtightness and thermal performance standards, could offset the initial upfront carbon through reduced operational carbon over time.

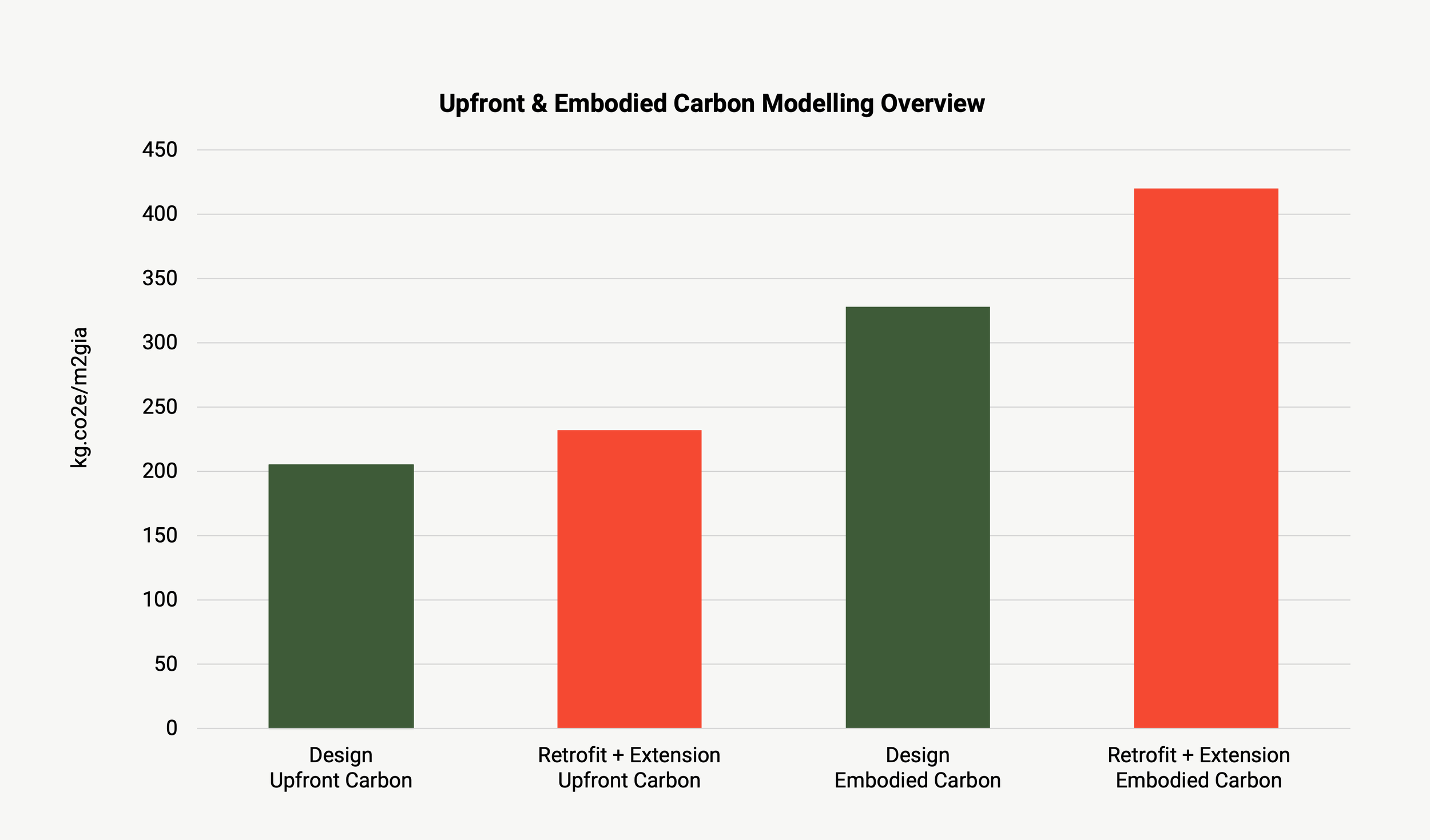

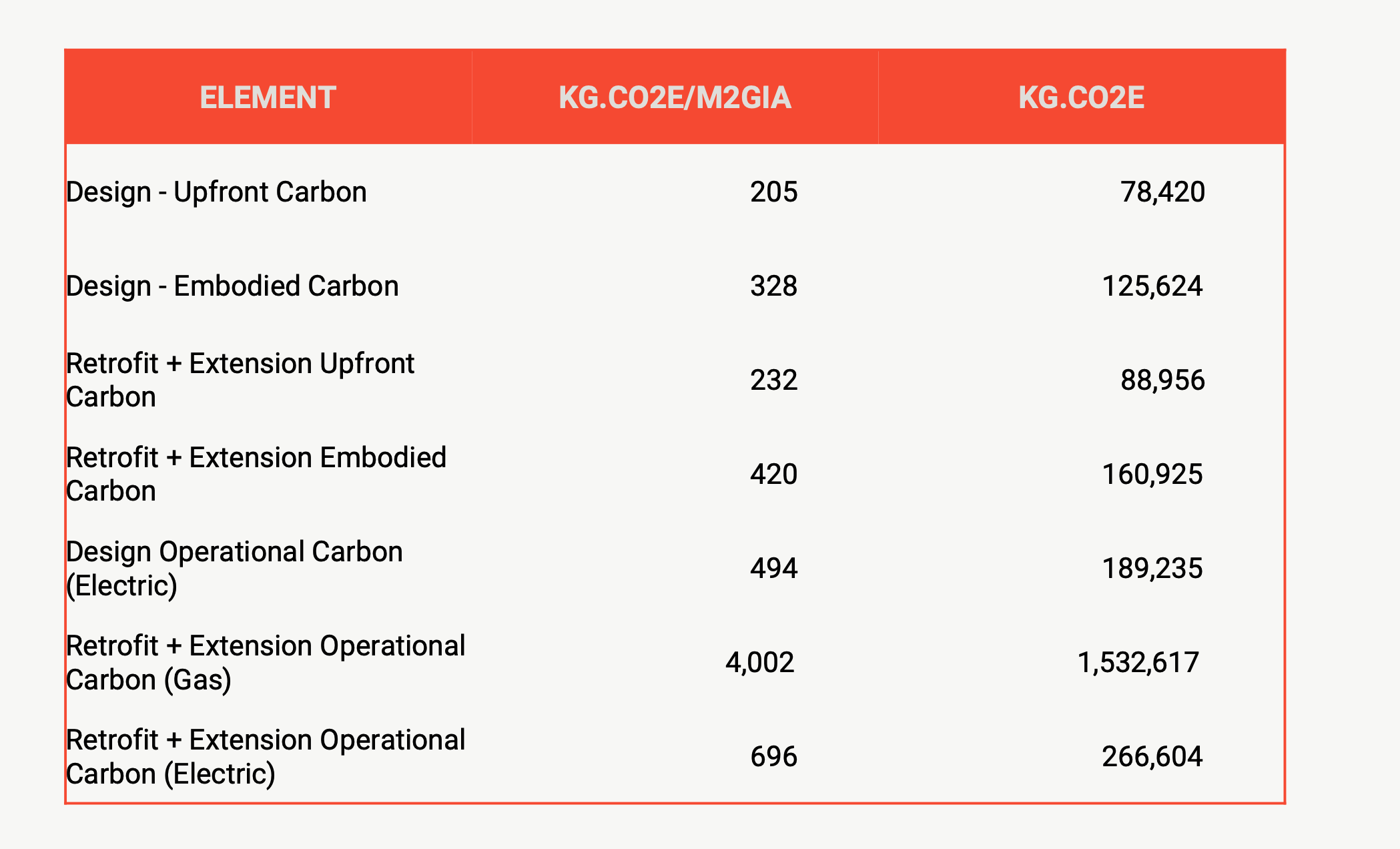

To help answer this question, Cook and Cardenas (link https://www.cookcardenas.co.uk/) were appointed to complete embodied carbon calculations, aligned with RICS Whole Life Carbon Modelling V2 at granularity level 1. Two scenarios were modelled.

Scenario 1 – New Build Dwelling:

The proposed design mirrors the PH15 construction system (link https://www.phhomes.co.uk/), which aims to deliver Passivhaus performance using an MMC approach with natural materials. The ground floor consists of a beam and block floor rather than a concrete-free foundation method. Heating is provided by heat pumps. While material reuse has been considered, primarily reused bricks in landscaping, this falls outside the scope of the modelling, in line with BCC and LETI guidance.

Scenario 2 – Retrofit and Extension:

The retrofit element aligns with Barefoot Architect’s typical approach to a “deep retrofit.” The extension matches the low U-value strategy of the proposed design but uses materials more typical of an extension, such as cavity walls, a ground slab, floor finishes, and a timber warm roof construction. Both reusing the existing gas boiler and installing a heat pump were examined for operational carbon.

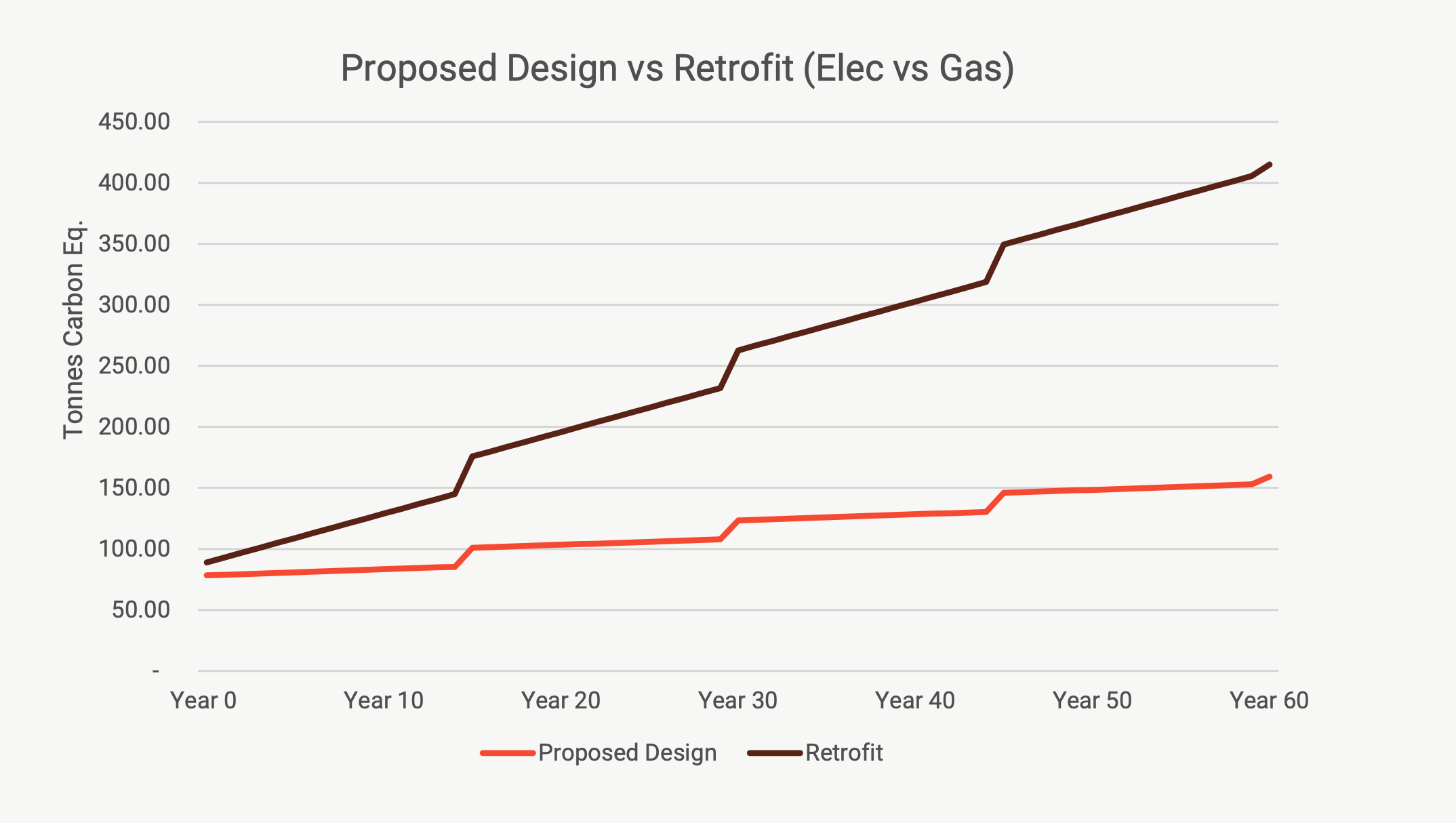

The results were surprising.

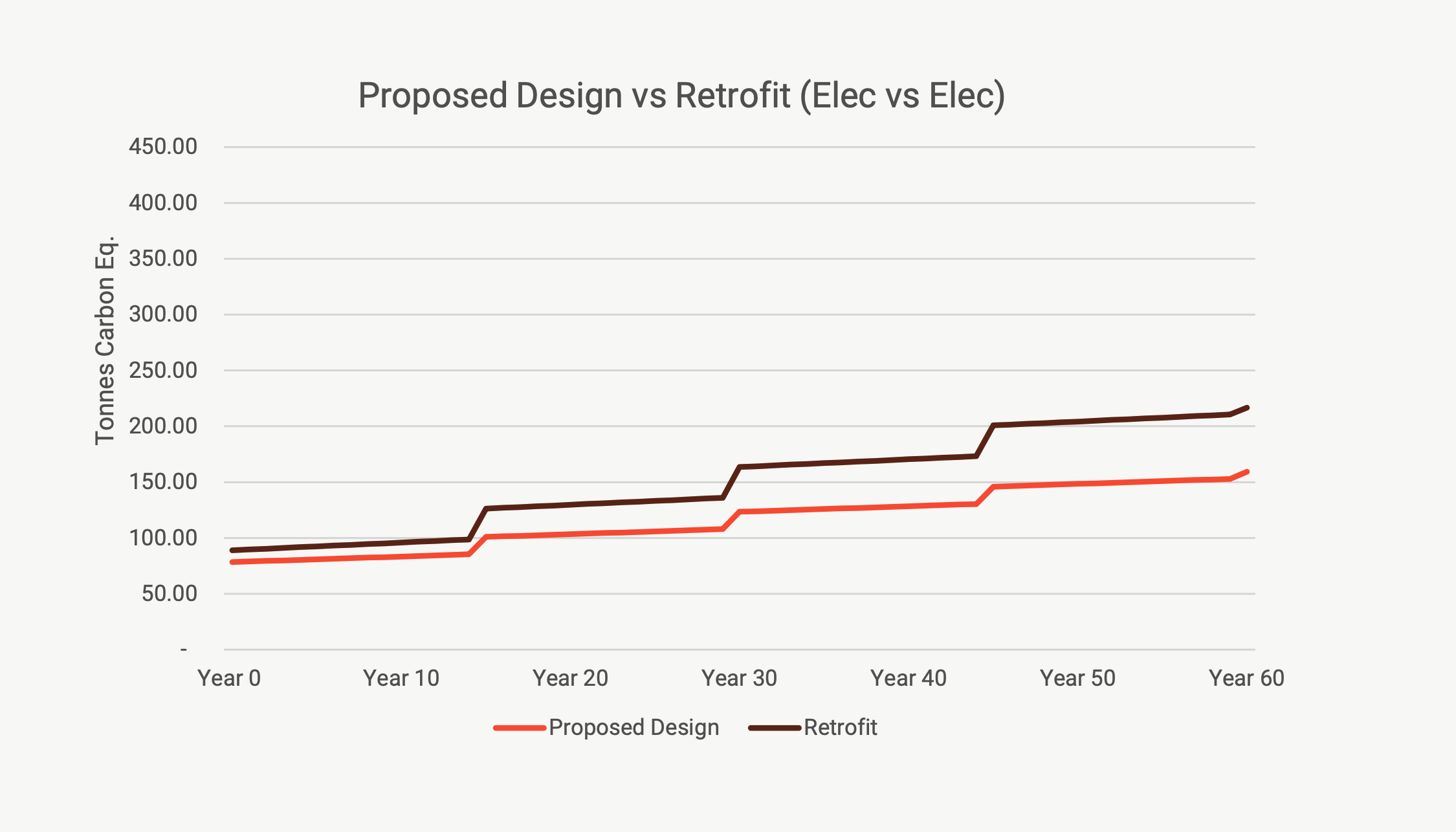

For both options - proposed design versus retrofit (gas) and retrofit (electric), the retrofit was more carbon-intensive in Year 0 than the proposed design. The low-carbon performance of the proposed design is driven using natural materials in the PH15 system, compared to the more typical construction materials used in the retrofit and extension.

Over the lifetime of the building, these gaps widen due to the lower operational carbon achievable with the PH15 system and the proposed design, compared to a typical deep retrofit. The upticks shown in the graphs represent material replacement averaged at 15-year intervals. This includes internal plant, floor finishes, and windows, all of which require replacement over the 60-year lifetime of the building. Replacement rates align with RICS V2.

Conclusion

While reusing existing buildings is often assumed to be the most sustainable option, our findings show that a carefully designed new build, using low-carbon natural materials and high-performance standards, can outperform a deep retrofit both in upfront and lifetime carbon terms. This challenges conventional thinking and highlights the importance of whole-life carbon analysis in making informed, climate-conscious design decisions.